Churches without seating

Many people are surprised when they walk into European churches and don’t see any pews. They wonder why they have been removed. Whenever I am doing a presentation on the history of church architecture, I explain that pews were a fourteenth century addition to church design. Often this is part of a discussion on whether chairs are an appropriate substitute for pews.

Many people are surprised when they walk into European churches and don’t see any pews. They wonder why they have been removed. Whenever I am doing a presentation on the history of church architecture, I explain that pews were a fourteenth century addition to church design. Often this is part of a discussion on whether chairs are an appropriate substitute for pews.

This recent article from the Aspen Group takes a different tack and talks about this topic in light of being open to departing from tradition and being open to change (something always worth discussing when talking about church design).

The article contains several quotes from James and Susan White’s 1998 book “Church Architecture: Building and Renovating for Christian Worship“. Rather than just discuss the history of seating in worship spaces, the authors discuss the impact of adding seating, noting what I believe is probably the most important impact – the change from being active participants to passive spectators. He writes:

“In the late Middle Ages, the congregation sat down on the job and there was a drastic change in Christian worship—perhaps the most important in history. People, in effect, became custodians of individual spaces which they occupied throughout the service, and social distinctions made some spaces more privileged than others.”

The article also quotes from Adam Graber’s ebook, From Pews to Podcasts: What Technology Wants for the Church, which explores how technology has shaped, and continues to shape, the church throughout history. In Chapter Two, entitled “Churches Without Chairs”, he writes:

“Without chairs, they had been actively involved and engaged by moving along with each element of the service, but as they sat down they became passive viewers—spectators in an audience. The service became something to watch.”

This whole idea of whether the congregation should consist of spectators or active participants was clearly addressed, at least for the Roman Catholic Church, by the Second Vatican Council in the early sixties. In the first official document to come out of the Council, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy states: “The Church earnestly desires that all the faithful be led to that full, conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations called for by the very nature of the liturgy.” (Par. 14)

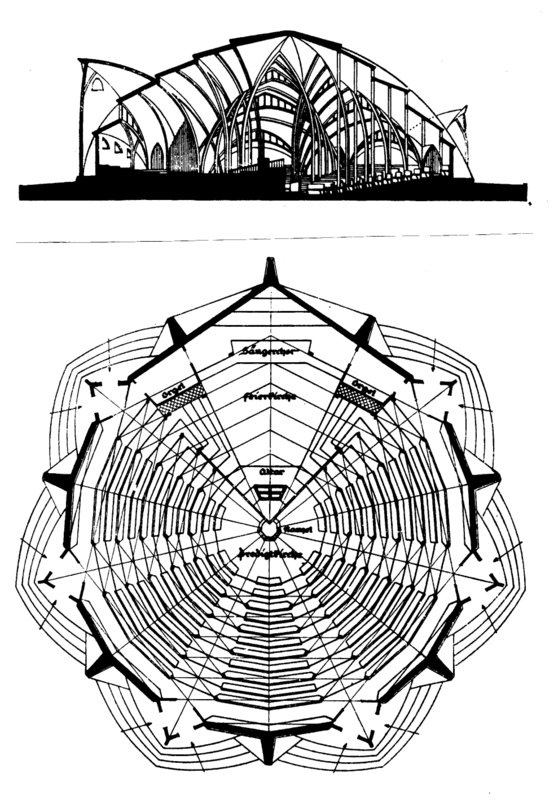

Perhaps the Catholic Church was trying to regain something that had been lost over the centuries, with the increasing separation between the clergy and the laity. According to Ed Sövik‘s book Architecture for Worship, published in 1973, German architect Otto Bartning seemed to have had similar concerns some forty years before the Second Vatican Council. He had proposed that the long and narrow processional or axial plans of traditional church buildings were inappropriate to current Christian understanding.

“The proper view of the gathered congregation, he said, is that of a cohesive community of clergy and laymen (all priests) whose members should be aware of their unity as the Body of Christ, the family of God, the household of believers. When they meet it is not as individuals at prayer, and not as a congregation of observers in attendance at a clerical ritual, but as a community acting together. …Bartning saw the circular room as the popular reflection of this understanding, for such an architectural shape not only symbolizes unity and coherence, but affectively (sic) encourages it. He made a model which he called “Stern Kirche” with altar at the center and a full ring of people about it. By now this image has been built many times, and its general propriety as a formal expression is broadly accepted.” (page 31)

Another forty years have passed since this statement by Mr. Sovik (a man who is credited with profoundly influencing church design for over 50 years), and things seem to be coming full circle (no pun intended). Although many Catholic churches have indeed been designed to encourage full, conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations, many contemporary Catholic churches are moving away from that directive.

The Counter-movement

As an avid observer of church architecture, I am always watching to see what is changing. Of course, not all of it is good, but it is all worth observing. Although axial plan churches have continued to be built over the last forty or fifty years, they were becoming fairly uncommon – at least for new, Catholic churches. That is until around 1990, when two men – one an investigative reporter and the other an architecture professor – helped start a movement away from the church design trend that had developed over the previous thirty years.

Michael S. Rose

The investigative reporter was a man named Michael S. Rose. According to his bio on CatholicCitizens.org, Mr. Rose “has illuminated a number of highly controversial issues in contemporary Catholicism, most notably the scandal surrounding unpopular remodeling of older Catholic churches and cathedrals across the U.S. His articles, editorials, and essays have appeared in venues such as Wall Street Journal, Catholic World Report, New Oxford Review, Homiletic & Pastoral Review, Envoy, Adoremus Bulletin, National Catholic Register, The Wanderer, Lay Witness, A.D. 2000, Challenge, This Rock, and Catholic Dossier.” His two books, The Renovation Manipulation: The Church Counter-Renovation Handbook (published in January 2000) and Ugly As Sin: Why They Changed Our Churches from Sacred Places to Meeting Spaces and How We Can Change Them Back Again (published in 2001) tapped into the frustration many Catholics felt about the renovations of their historic, traditional churches. In the second book, he expands his critique of “wreckovations“, as he liked to call the renovations, to new church design. Here are the first two lines from the description on the Amazon page for this book:

“The problem with new-style churches isn’t just that they’re ugly – they actually distort the Faith and lead Catholics away from Catholicism.

So argues Michael S. Rose in these eye-opening pages, which banish forever the notion that lovers of traditional-style churches are motivated simply by taste or nostalgia.”

Duncan Stroik

Ten years earlier, Duncan Stroik, Yale ’87 (M. Arch), joined the Notre Dame School of Architecture as a founding faculty member of the school’s classical program. In his academic work, Stroik has advocated beauty and tradition as the standards of architecture. In that same year Stroik founded his firm Duncan G. Stroik Architect LLC. His work continues the tradition of classical and Palladian architecture, also known as New Classical Architecture. In 1998, Professor Stroik founded the Institute for Sacred Architecture and the Sacred Architecture Journal as editor. The Institute for Sacred Architecture is a non-profit organization that is dedicated to a renewal of beauty in contemporary church design.

Both of these gentlemen seem to view a return to tradition as a return to beauty. While Mr. Rose has moved on from church architecture to other topics affecting the Catholic Church, Mr. Stroik has been extremely busy designing Roman Catholic houses of worship. A review of the portfolio on his website shows the New Classical church designs he and other firms like his are well known for. Wikipedia describes New Classical architecture as a contemporary movement in architecture that continues the practice of classical and traditional architecture. It is this focus on tradition that brings us back to the topic of church seating.

The Return to the Axial Plan

Despite the fact that they have only been around since the 14th century and did not and still do not exist in many early churches, seating in churches – particularly pews – are seen as part of a traditional design for a church. And arranging those pews along a long, central axis makes the church feel even more traditional. I would venture to say that the prototypical church to most people is a long, rectangular building with a raised area at one end with a pulpit or altar and rows of seats along a central aisle. I suppose that has to do with the preponderance of churches designed that way. I can easily understand why that is the first image to come to mind for most people. What is hard for me to understand is why architects are still building Catholic churches that way. Every principle of good liturgical design suggests that a long, rectangular building with rows of pews along an aisle is probably not the best solution. Yet they continue to be built, continue to be published and continue to win awards.

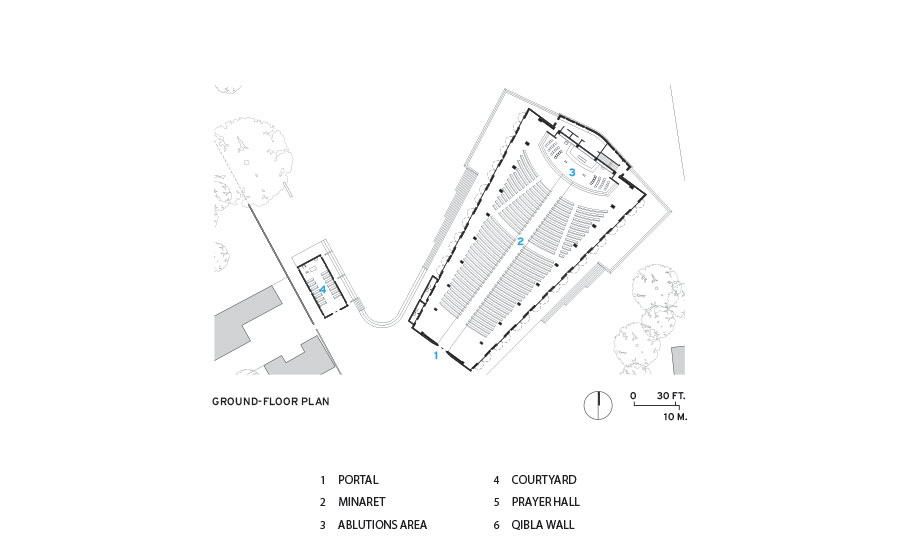

The May 2016 issue of Architectural Record included a section on Sacred Spaces, which described two Catholic Churches, a mosque, a synagogue and a temple. The first Catholic Church, in Frommern, Germany, while small, does provide seating on three sides of the altar platform – most of it in fixed pews but some of it using moveable benches. The second Catholic Church – the new Kericho’s Sacred Heart Cathedral in Kenya – was designed by a firm with no previous experience in Catholic Church design. While the church has many redeeming qualities, to me, it seems that the layout is completely inappropriate for a Catholic African worshiping community. With 36 rows of pews, it would be virtually impossible for the back half of the church to feel any connection to the liturgical action, let alone a connection to each other. Although I am sure the community is grateful for their new worship space, I feel that an opportunity has been missed that they will never regain.

Interestingly, the introduction to this section of the magazine states that “While providing contemplative settings for meditation and prayer, houses of worship–whatever the faith–must also respond to the wide-ranging programmatic needs of the people they serve.” I couldn’t agree more. But it seems to me that both examples published seem to focus more on the first part of that sentence than the second part. I believe that it is possible to design excellent buildings for worship that meet both parts of that equation and I am personally committed to carrying on the vision of my predecessors in this work.

1 Comment

For a good article on seating options in contemporary worship spaces, check out this article from Worship Facilities magazine: http://www.worshipfacilities.com/article/seating_configuration_and_the_worship_experience

1 Trackback